April 2019

Animal Jewellery: Why Going Wild is always the most interesting

CONTENTS

♦ Why we love animal jewellery

♦ Animal jewellery and its symbolism in culture

♦ From the Egyptians to Art Deco: Our favourite eras in the history of animal jewellery

♦ Four great stories of animal symbolism

♦ What is your spirit animal?

♦ Commissioning bespoke animal jewellery

WHY WE LOVE ANIMAL JEWELLERY

Tessa Packard’s love of nature started at a very young age. Growing up in both London and the countryside, her experiences with wildlife oscillated between the wilds of Scotland and the Natural History Museum (an institution she still calls ‘her second home’ in the capital). Although very different, Tessa attributes both these locations as being extremely instrumental and formative playgrounds in her youth, shaping who she is and what she loves today.

Unsurprisingly, nature and animals enjoy a centre stage role in Tessa Packard London’s fine jewellery. From bee jewellery to pig jewellery and insect-filled secret gardens, Tessa has tackled a large number of animal subjects over the years, the most famous series being perhaps her porcelain animal earrings. These one-of-a-kind creations feature a different porcelain creature each time, paired lovingly with gemstones and metal detailing to create statement mis-matching earrings. Whimsical, fun and utterly memorable, they embody a child-like, fairy-tale fascination with the natural world, which is very typical of Tessa’s brand DNA.

Other statement animal earrings in our current collections include the Fire Wasp Earrings, carved from amber and set with faceted amethyst; the one-of-a-kind Rock Pool Earrings featuring miniature crabs and citrine tops; and the summery, octopus Positano Earrings, inspired by holidays on the Amalfi coast.

ANIMAL JEWELLERY AND ITS SYMBOLISM IN CULTURE

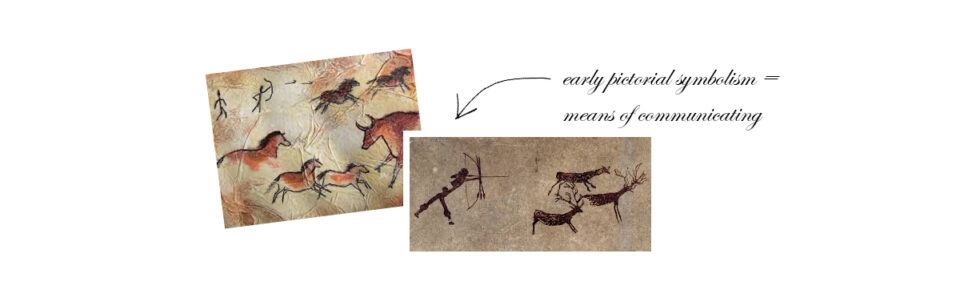

Human relationships with wildlife have existed since the birth of mankind. This enduring relationship is responsible for the rich (and often complex) tapestry of animal symbolism we see today.

In the early days, before the invention of the written word, animal symbolism (like all symbolism) was particularly important for survival. Forms of communication for food and shelter depended on it. As folklore and literacy developed, the animal form became more ‘meaningful’ in the human mind. A bear didn’t just mean angry, dangerous beast (Stay away! Be prepared! Let’s hunt bear!) – it was now understood to represented certain human traits, such as strength and valour.

The first examples of symbolic animal jewellery came in the form of a found feather, animal tooth or carved rock, worn by prehistoric man around their neck for reasons of beauty, protection or ritual. Over time, the meanings behind animal-themed jewellery diversified as humans became more sophisticated to include:

♦ Currency – ie. jewellery serving as a type of currency or tool in trading

♦ Wealth security – ie. valuable jewellery providing its owners a source of wealth security or investment

♦ Status – ie. jewellery to represent a person’s social standing or personal wealth

♦ Religion – ie. jewellery that serves either a religious purpose or symbolises a person’s denomination

♦ Fashion – ie. jewellery that demonstrates a person’s sophisticated tastes

♦ Self Expression – ie. jewellery that shows off personal style or makes a statement about the wearer

♦ Relationships – ie. jewellery that speaks of commitment to a person, place, country or community

♦ Rites of Passage – ie. jewellery that symbolises a milestone in a person’s life

FROM THE EGYPTIANS TO ART DECO:

OUR FAVOURITE ERAS IN HISTORY FOR ANIMAL JEWELLERY

THE DAWN OF MANKIND

The very first examples of jewellery were made over 135,000 years ago from organic and animal found matter, such as shells, feathers, seed pods, antlers and bone; and in fact, is actually very likely that prehistoric man decorated the body with this type of natural jewellery before the advent of clothing.

Some of the most important archaeological discoveries of prehistoric ‘jewellery’ over recent history include:

♦ A necklace or bracelet made from eagle talons found in a Neanderthal cave in Croatia.

Until their discovery in 2013, many scientists had assumed that Neanderthals were incapable of harnessing the sophisticated, symbolic thinking required to make and wear jewellery. This artefact challenged these long-established beliefs about early man, indicating that they were actually more developed than first thought, able to ascribe aesthetic importance to decorative adornments.

♦ 100,000 year old Palaeolithic nassarius shell beads from Northern Africa.

The earliest of these beads were found in Israel and indicate that the Palaeolithic people used these sea snail beads not only for decoration but also in trade.

♦ A Siberian chlorite bracelet dating from 70,000 years ago.

Its discovery is unique because it was made by the Denisovan people – an extinct species of human older (and separate) from the Neanderthals. The bracelet was unearthed next to a skeleton of a mammoth and seven year old girl, implying that the Denisovans gave sacred or ceremonial significance to jewellery, again something that was not believed to be true previously.

♦ Ostrich egg beads dating back 40,000 years ago, unearthed across the eastern coast of Africa.

Uniform in colour, size and shape, these beads demonstrate a civilization with a sophisticated design aesthetic and social value.

♦ A golden bead dating from 4600BC.

This object is considered to be the earliest example of gold jewellery discovered to date, predating the equally famous Varna site in Bulgaria.

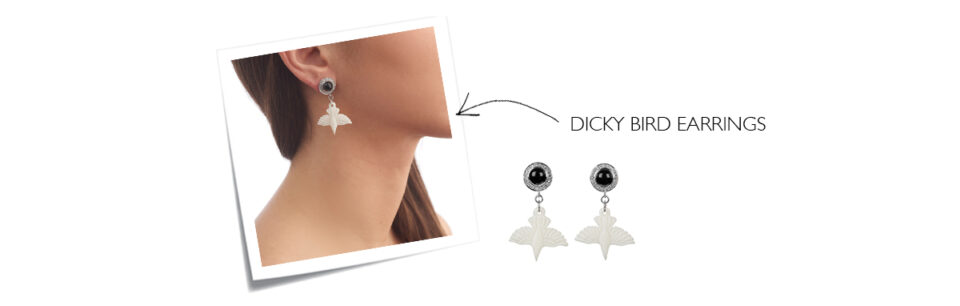

As a brand that likes to use unusual, natural objects in their jewellery, prehistoric jewellery has always been a source of inspiration for us, especially in the case of our 18ct white gold, onyx and diamond Dicky Bird Earrings. Hailing from our Lost & Found collection (inspired by Victorian curiosity cabinets, Joseph Cornell and found objects) these delightful, unique earrings feature hand-carved buffalo bone bird drops, found once upon a time at an antique market stall.

AROUND THE STONE AGE

Once the art of stone carving (and later metal work) had become established, bodily adornments in the shape of animals and insects became commonplace, initially in the form of afterlife accessories. In fact, the history of early jewellery design – what came first and what came next – is really understood thanks to this custom of burying the dead with their richest ornaments.

One of our favourite animal figurines can be traced back 4,500 years ago to the Sumerians, who in c.2600BC buried their queen Pu-abi at Ur in Sumer (now called Tall al-Muqayyar) in a robe made of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, carnelian, agate and chalcedony beads, alongside three gold and lapis lazuli fish amulets and the most beautiful trinket in the form of two seated gazelles. Although made so long ago, we love the way these animals are depicted so accurately; their chunky weight and matt finish almost make them look contemporary, like modern pieces of art.

THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS

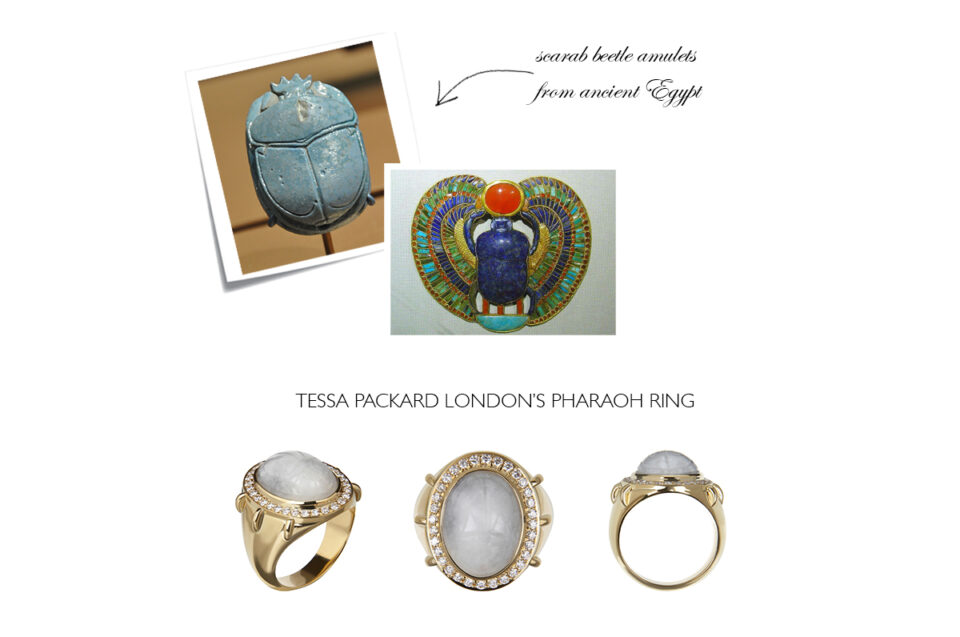

The Egyptians were also early adopters of animal jewellery. The sensational discovery of the pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb in the 1920s revealed a bounty of treasure dating from 1332BC – 1323BC. Included in this hoard of diadems, necklaces, pectorals, pendants, bracelets, earrings and rings were several pieces depicting the scarab beetle, the falcon, the serpent, vulture and sphinx – animals iconic and unique to ancient Egypt’s visual and religious culture.

Of all the Egyptian animals, the scarab beetle has always been a favourite of ours as a symbol of immortality, resurrection and the morning sun. In ancient times, the scarab beetle was often placed on the chest of a mummy to represent the heart of the deceased. They were also used frequently in seals, with the name or place of the owner engraved around or alongside the scarab motif. Our very own Pharaoh Ring is inspired by the practice of these scarab-seal rings. It features a hand-carved jadeite scarab cabochon set in gold with pave-diamond detailing surrounding the scarab to accentuate its form.

Interestingly, the ancient Egyptians also regularly took up the practice of depicting humans as part animals, marrying a man’s torso and legs with a falcon’s head for example. These hybrid fusions can be seen depicted across all Egyptian decorative arts, no more clearly than in this engraved gold amulet on display at the British Museum. It delicately illustrates a lion-headed man inset inside a feather-headed man with a fish drawn below.

THE MINOANS

The Bronze Age civilizations that simultaneously flourished on the Mediterranean island of Crete (and expanded through the Aegean) embraced a joyous and vibrant representation of nature. Using flowing, expressive shapes and forms the Minoans crafted extremely intricate and technologically sophisticated pieces of jewellery, the Bee Pendant of Mallia (c.1500BC) and the Master of Animals Pendant from Aegina (c.1500BC) being perhaps two of the most notable examples.

The Master of Animals pendant is made of gold and consists of what appears to be a god clasping the neck of a wading bird or goose in each hand. The centre ensemble is encircled by a further two serpents on each side and the form of three spread-winged birds below.

The Bee Pendant also demonstrates the full repertoire of Minoan goldsmith skills from this era. It is rendered in great detail and realism, depicting two bees clutching delicately between them a drop of precious honey, which they are about to deposit into a circular, granulated honeycomb.

In 2015, Tessa herself designed a collection of honeycomb and bee jewellery inspired by this symbolic animal. Named Predator/Prey, the collection looked to explore the kinetic relationship between insect and man – how one affected the other’s movements. Several pieces – including gold bee earrings and a long, lariat bee necklace – integrated specifically placed links to emphasise this aspect. Even today, our bee charm is still one of the most popular designs from the collections.

Click HERE to shop our bee jewellery collection

ANCIENT ROME

The ancient Romans loved to deck themselves in jewellery, and to an extent never seen before. The breadth of Mediterranean territories under Roman control allowed this ancient civilization to really exploit a wide range of natural resources and goldsmithing skills, as well as benefit from extensive trade routes with the East, giving them access to exotic materials and a wide range of precious stones not native to Europe.

With regards to animal jewellery, the snake or serpent motif was particularly popular, and regularly used as inspiration for bracelets, rings and arm bands. Intaglios (a design engraved or incised into a material, such as stone) were also often engraved with animal forms, and many examples depicting parrots, dolphins, dogs and storks were commonplace at that time and can be still be seen today in the collections of the British Museum.

This ancient tradition of animal engraving has influenced many modern-day jewellers, including us at Tessa Packard London. Carved gemstones remain one of our favourite things to collect for jewellery making; and metal engraving is still to this day one of the easiest and most popular ways of quickly personalising rings, metal pendants, trophies and celebratory plaques. A Couple of examples of stone carved pieces from our jewellery collection include the Whoops-a-Daisy Ring and Bee-utiful Earrings.

THE DARK AGES

The jewellery worn in medieval Europe between c.1200AD and c.1500AD reflected an intensely hierarchical and status-conscious society. Gold and gemstones were used to show off high rank and nobility, with those further down the social pyramid wearing jewellery only made from base metals, such as copper or pewter.

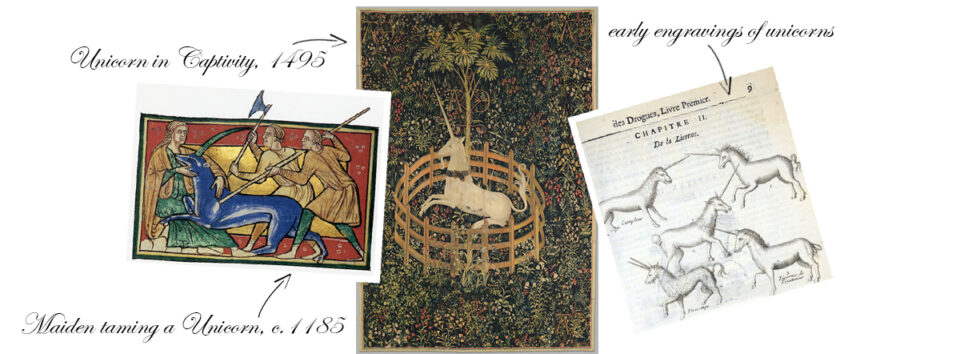

The figurative or realistic representation of animals in jewellery during this period was much less common, and those creatures that were depicted in detail were often mythological in nature, such the dragon or unicorn.

The unicorn was probably one of the most highly regarded animals in Medieval times. Not only a symbol of fierceness, tenderness and purity, it was also seen as an emblem of Christ, the Church and chastity. In wedding portraits, its magical form represented faith, matters of the heart and the taming of the beloved. Although no one quite knew where the unicorn resided in Medieval times (with Western scholars claiming it was native to as far reaching places as Mount Sinai and the Americas), what is clear is that this magical beast was depicted in both art and literature the world over, with representations found in the Middle East, Asia and beyond.

The most famous example of unicorn art from this era is probably the Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries – a series of seven tapestries that depict noblemen and hunters in pursuit of a unicorn through idealised French landscape. Whilst no one quite knows who made them and what they exactly mean, they are believed to be French in origin and explore such themes as Christianity winning over paganism, the taming of human love by Christ, and the subjugation of love in marriage.

Whatever the real meaning is, we love this enigmatic group of works and this mythical beast. The more magical horses in our life the better.

THE RENAISSANCE

The Renaissance period (c.1400AD – c.1600AD) elevated jewellery to an art form comparable with the most revered of the figurative arts. In fact, there really was no division between jewellery, painting, architecture and sculpture at this time – nearly all the most famous Renaissance artists were experienced goldsmiths and visa-versa.

The key themes in jewellery at this time were religion and earthly power, with pieces designed to be statements of political authority or bodily strength. One such example is an Italian 15th Century scorpion ring – currently housed at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London – which contains at its centre a carved Roman or Greek stone from the 2nd or 1st Century BC. The scorpion was believed to be a symbol of physical protection, with the ability to heal patients from poisoning and soothe fever as a water zodiac sign. No doubt the owner of this ring hoped this accessory would bring him long-term good health at a time in history where an early death was common.

Another customary Renaissance tradition in jewellery was the creative transformation of irregular, baroque-shaped pearls into animals or human-animal hybrids. The rise of Humanism during the Renaissance period championed the study of ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, poetry and art, in turn inspiring goldsmiths to explore and depict the natural world through a mythological lens. Women riding seahorses, emerald eating salamanders, centaurs, sea monsters and jewel-encrusted mermen were amongst the many subjects represented. Three such important examples are a rabbit pendant from the Wallace Collection, London; a donkey pendant from the British Museum; and the Canning Jewel, once owned by the ruling Medicis of Florence.

Interestingly, there was also another added dimension to animals and jewellery in this era: a strange imagined belief that a surprising number of gemstones originated inside the body of animals. According to Stephen Bateman’s 1582 translation of Bartholomaeus Angelicus (which lists a number of stones rarely or never heard of before) noset is ‘taken out of a Toads head’, reyben is found ‘in a Crabs head’ and another unnamed stone ‘growthe in ye Snail’. No one knows what the modern name for nosset or reyben would be – or if these gemstones were completely made up ones – to this day it remains a gemological mystery.

1600s, 1700s AND EARLY 1800s

By the end of the 17th Century jewellery was decidedly different in look and feel from that of the Renaissance. Not only had faceted stones become de rigueur (due to advanced cutting techniques), but a great vogue for cultivated flowers began, resulting in an increased demand for ornamental motifs of garlands, knots, ribbons and scrolls in the fine jewellery of the day.

Other figurative decoration almost completely disappeared in favour of these new designs, and it wasn’t truly until the very late 18th Century that animals in jewellery began to steadily reappear, thanks in part to the archaeological discoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum, which inspired artists to look back once again to ancient designs. This, alongside the impact of the Industrial Revolution, brought about a change in European tastes. Against the polluted backdrop of urbanisation and a heightened technological age, nature became a popular visual alternative, especially for the middle classes, whose romantic fascination with animals and insects led them to become popular motifs in jewellery once more.

Amongst the most popular animal motifs of the late Georgian and early Victorian time were birds and butterflies in flight, dogs, serpents and insects, their bodies often fully mounted in old cut diamonds or pearls to create extremely intricate sculptures in miniature.

ARTS & CRAFTS AND ART NOUVEAU

The Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau movements that developed towards the end of the 19th Century were based on a profound unease with the new modernised world. Its jewellers rejected machine-led manufacture in favour of more traditional, hand-crafting methods. This process, they believed, would improve the soul of the goldsmith, his designs and the integrity of the final piece.

Unsurprisingly, the animal kingdom was a rich source of inspiration for the artisans in question, and for none more so than C.R. Ashbee, founder of the Guild of Handicraft in London in 1888. An innovative architect, furniture designer and jeweller, Ashbee’s favourite and most distinctive motif was that of the regal peacock. One of his most celebrated works is a pendant brooch he made for his wife Janet in c.1900 depicting a front-on peacock with pearl-set, extended tail feathers (now housed at the Victoria & Albert Museum).

Insects were a real favourite amongst the Art Nouveau jewellery designers. Their iridescent wings and richly hued bodies served as ideal sources of inspiration for enamel work (an extremely popular technique of the day). One of the most important Art Nouveau jewellery designers was Rene Lalique (1860 – 1945), whose magical, sculptural creations successfully combined a wide range of new materials (such as mother-of-pearl) with enamel and precious gemstones. Extremely collectable, one of his most notable pendants Quatre Libellules (c.1903) sold at Sotheby’s in 2015 for $212,000.

THE ROARING TWENTIES

Although affected by war and depression, jewellery design between the 1920s and 1950s continued to innovate and inspire. Animal jewellery, however, did not prosper in these decades as stylistic trends tended to favour the nonfigurative – those that were emblematic of modernity and development (such as Cubism, Futurism and the Bauhaus Group). As a result, Art Deco jewellery is typically all about clean lines, geometric motifs, symmetrical patterns and minimal figurative forms.

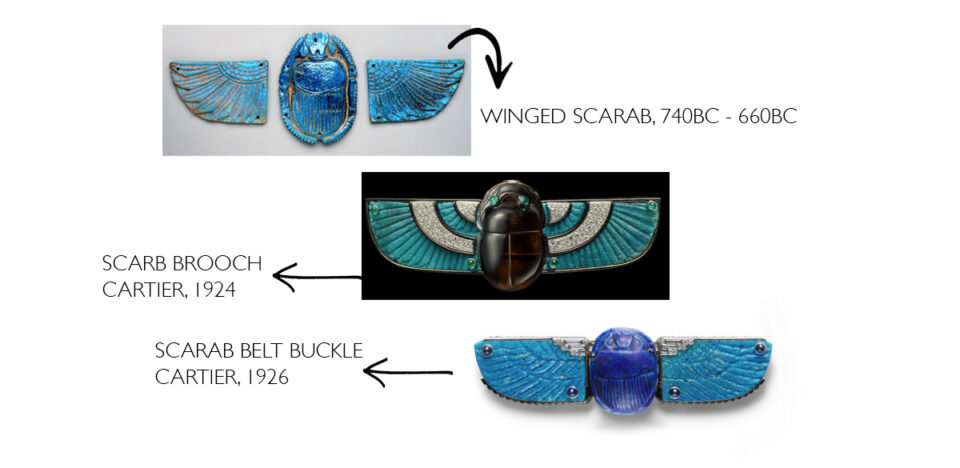

One set of creatures did, however, continue to court favour throughout the Art Deco period: those from ancient Egypt. Demand for Egyptian style designs boomed after the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, and motifs such as the scarab beetle, falcon and hound became once again extremely desirable to wear at dinner parties and high society events under the trend of ‘Egyptian-revival’.

THE MID-20th CENTURY

The subsequent decades of the 1940s, 50s and 60s were a golden age for animal jewellery. Artists from all corners of the western world enthusiastically – and relentlessly – crafted bejewelled and enamelled creatures to meet public demand for their ever-popular animal jewellery collections.

Arguably the most notable animal motifs from this period are the Chaumet bee, the Cartier panther and the Bulgari serpent. Whilst each of their beginnings can be attributed to an earlier period in the brands’ history, it was really only the start of the 1940s that saw each of these animals come into their own, enjoying immense attention by press, clients and celebrities alike.

Other important jewellers of the day include Seamen Schepps and the internationally-fabled Suzanne Belperron. Equally mesmerised with the natural world, they are celebrated for their novel and tactile approach to animal representation – in each case throwing out the rule book and depicting nature through their own unique lens.

Belperron’s approach to form and composition was sculptural, innovative and above all modern. In complete contrast to her earlier Art Deco works, Belperron’s mid-century jewellery was free of fiddly detail or delicate metalwork. It embraced new materials, such as wood and quartz, and was apologetically colourful and bold. Amongst her many masterpieces is a chalcedony, pearl and diamond starfish brooch (c.1939) that demonstrates very emphatically her signature style during this time.

Seamen Schepps also explored sea creatures amongst others, rendering many versions of his own starfish brooch in a variety of metals and stones. Perhaps what is most interesting about this jeweller is that he wasn’t just inspired by animals – he also used organic animal material to create his works. His most famous example of this is the series of shell earrings and cufflinks he designed. The combination of polished precious metal, sparkling gemstone and iridescent shell proved to be both ground-breaking and highly commercial. His shell jewellery is still widely collected today.

CONTEMPORARY ANIMAL JEWELLERY

The popularity of animals in jewellery has continued through the 20th Century and firmly into the 21st. Today, this theme remains one of the most fertile sources for inspiration, occupying the mind of both mass-market, fashion jewellers and haute-joaillerie designers alike.

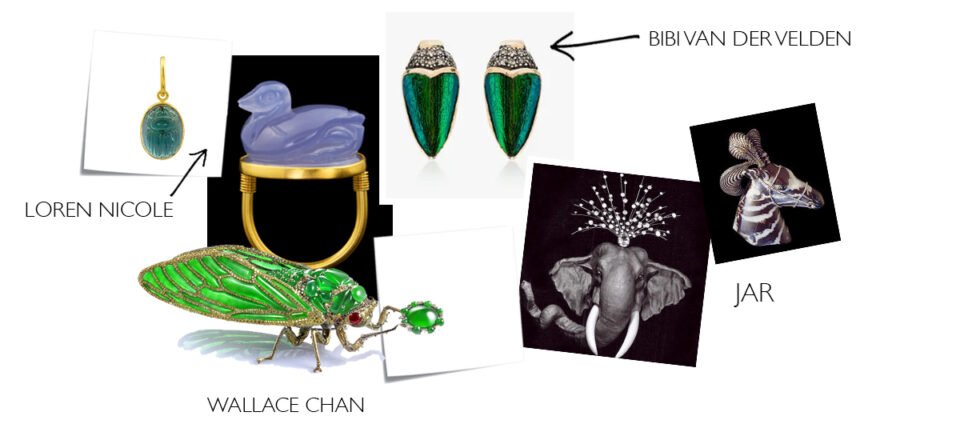

What has, however, become evident in recent decades is that there are no longer set, identifiable or specific trends in the world of contemporary animal jewellery. Some, like Loren Nicole, choose to look back to the ancients and create animal pieces inspired by the Egyptians; a handful of jewellers enthusiastically incorporate animal parts into their jewellery, such as Bibi van der Velden’s scarab wing and mammoth bone creations; others, such as Wallace Chan have blurred the lines between jewellery and sculpture by creating animal pieces that appear unwearable due to size or delicacy. In short, there is a style of animal jewellery for everyone, whether your tastes are hyper-modern or more firmly rooted in the past.

FOUR GREAT STORIES OF ANIMAL SYMBOLISM

THE TERRIBLE TUDORS

During the Tudor and Elizabethan times, animal symbolism was one of the most efficient means of communication. Coats of arms, banners, badges and portraits were carefully designed to convey a specific story about a family, an estate, a principality, guild or ruler. Queen Jane Seymour (one of Henry VIII’s many wives) used the form of a phoenix as one of her insignias as it represented resurrection, endurance and eternal life; Anne Boleyn, by contrast, chose the falcon as a metaphor for the eager pursuit of the desired.

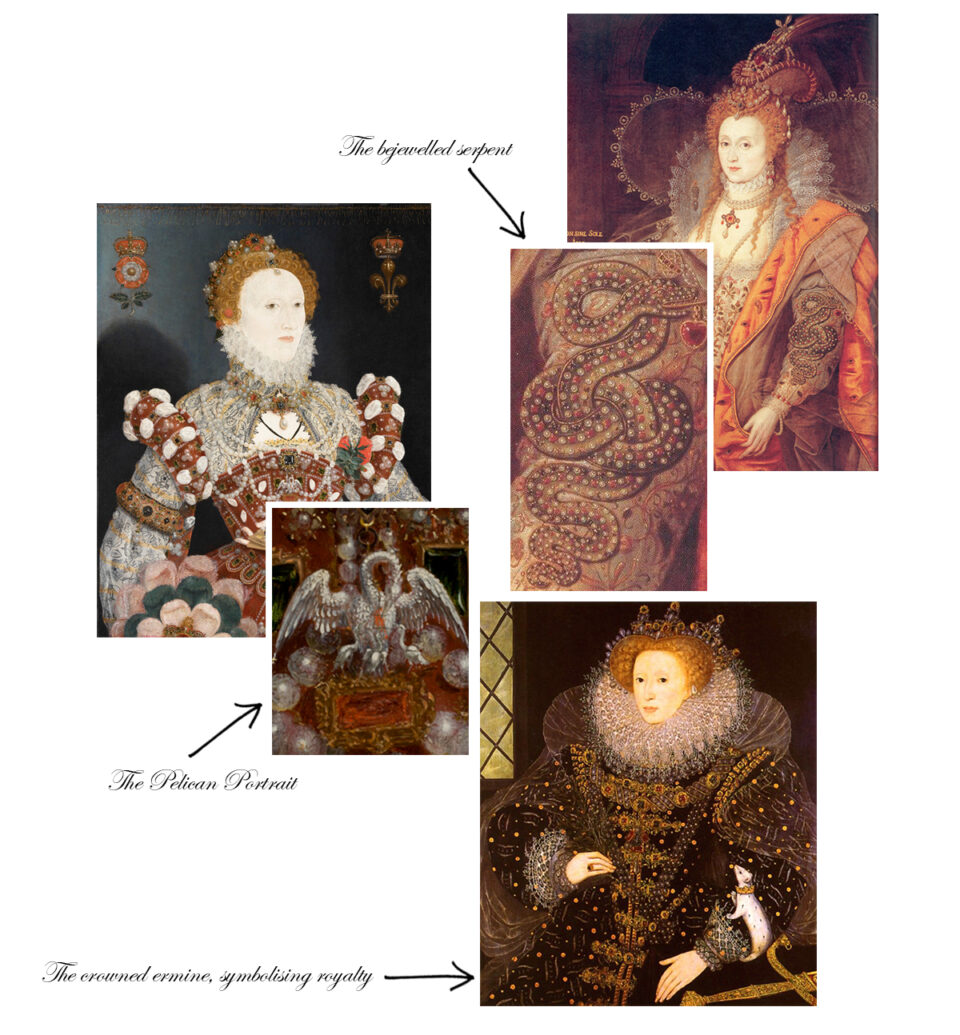

Elizabeth I was the queen of symbols and over her lifetime she chose three very different animals to best represent her reign: the snake, the ermine and the pelican.

One of the best examples of snake symbolism can be found in the Rainbow Portrait, painted in or around 1600 when the queen was in her sixties. Coiled on her sleeve in the richest of embroideries lies a gem-encrusted snake holding a red heart-shaped stone in its mouth. An ancient symbol of wisdom and cunning, the snake was no doubt meant to be understood as a metaphor for herself as an experienced and wise ruler who could not be tricked.

In a number of other portraits Queen Elizabeth I can be seen sporting a pelican motif, the most famous being Pelican portrait (c.1580s, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool) where she is shown wearing a delicate pendant around her neck. Traditionally a symbol of love and self-sacrifice, it was often paired visually (in both the jewellery and portraiture of the time) with pearls to further emphasise selflessness and purity of mind.

The ermine too was a symbol of purity during Queen Elizabeth I’s reign. According to legend, the ermine was an animal that would rather die than soil its pure white coat. Like the pelican, it features in a number of royal paintings, such as the Ermine Portrait by Nicholas Hilliard (c.1585), where it is shown wearing a gold crown around its neck as symbol of status and power (thus affirming the cultural norms of the time that ermine was to be worn by royalty and nobility only).

KING OF THE JUNGLE

The lion is another well recognised animal in decorative culture. Representing courage, protection, strength and leadership, the ‘king of the jungle’ was often depicted in jewellery to convey valour and heroism on the part of the wearer.

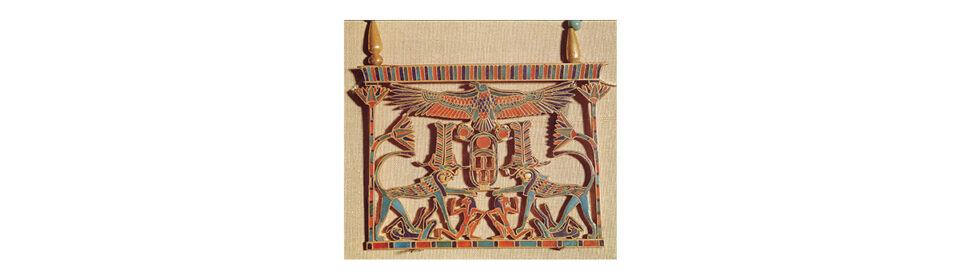

One such important example of lion jewellery is the Sesostris III pectoral. Here, Sesostris III (ruler of Egypt between 1836BC – 1818BC) is represented by two facing lions with plumed falcon heads. A vulture, with open, spread wings protectively shadows both lions overhead. This commemorative pendant is believed to depict Sesostris’s victorious defeat of the Nubians and Libyans, the vulture symbolising the protective lands of Egypt. Ancient dedicatory pectorals, such as this one, were often exclusively symbolic with very little narrative or figurative realism depicted within them.

16th CENTURY INDIA

Before the Mughal invasion of 1526, the north of the Indian subcontinent was divided into several Hindu kingdoms, many of which were extremely sophisticated in their visual culture. The use of bird and animal motifs was a popular theme in these pre-Mughal times, influenced predominantly by the religious and superstitious beliefs of the native people, with serpents, fish and peacocks amongst the most popular for use in jewellery (especially as neck, ear, nose and head ornaments).

Unlike the visual language of Europe, the serpent in this south-eastern culture signified quick potency and eternal return – the idea that the universe and all existence and energy is re-incarnated infinitely. Fish, by contrast, were one of the incarnations of Vishnu, the Hindu god, as well as being a symbol of abundance; and the peacock a representation of immortality.

Other such animals as lions and elephants were used profusely too, with the former representing strength, courage and sovereignty and the latter denoting visibility, calmness and gentleness. The lion-face motif – or kirtimukha – was particularly popular among southern Indian jewellery of the age. Created from the anger of Shiva, this religious symbol helped spread the philosophy of suffering, nirvana and re-incarnation across India.

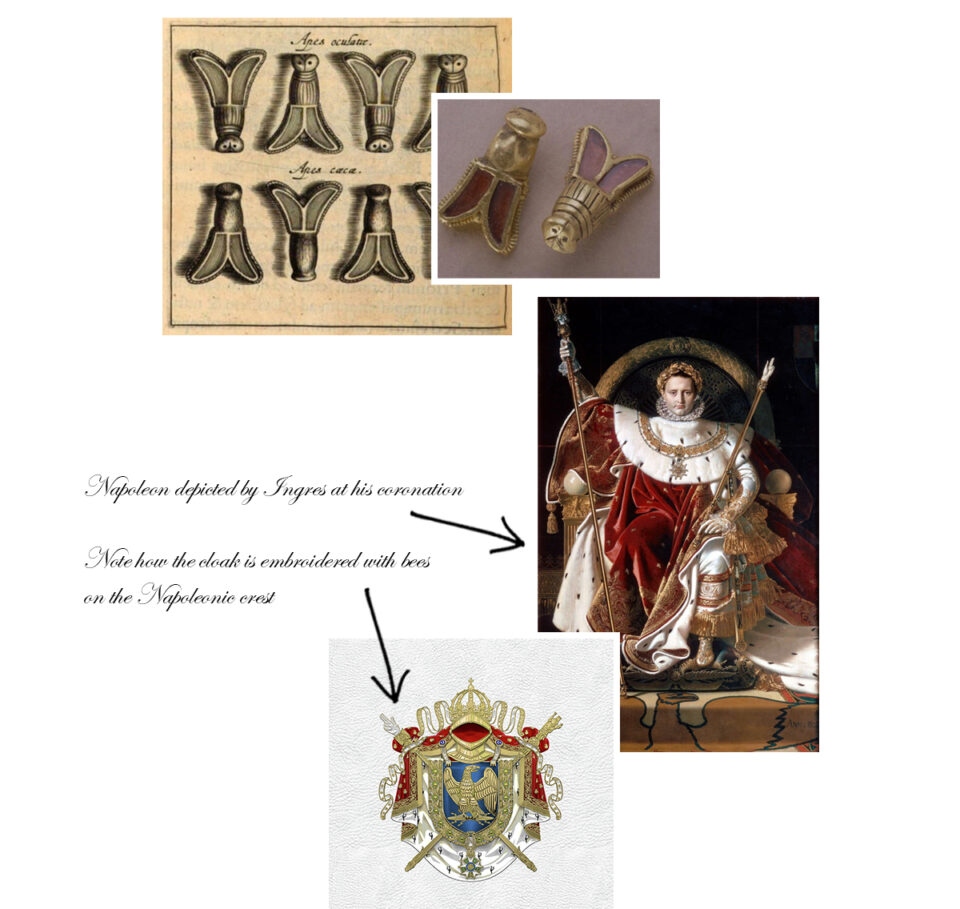

NAPOLEON’S BUSY BEES

In the history of jewellery, the bee is perhaps one of the most frequently depicted animals. Because of its hierarchical, socially organised and efficient nature, the bee has always been a favourite motif amongst the ruling classes who have used it as a symbol of diligence, compliance, sociability and hard work across many millennia.

One such example is the Merovingian Bees of Belgium, discovered in the tomb of Childreric, king of the Salian Franks from 457 to 481. Discovered by construction workers in 1653, these gold and garnet bees were given to Archduke Leopold William of Hapsburg and later presented to King Louis XIV of France in 1665 as a diplomatic gift.

Upon seeing these bees, Napoleon adopted them for himself as a symbol of the French Empire. His coronation in 1804 saw him crowned in a robe decorated with 300 gold bees, leading to his inevitable nickname of ‘the bee’. Napoleon’s choice of this emblematic insect was more than an aesthetic one – it was a highly considered political statement. Not only was the bee a blatant rejection of the Bourbon monarchy’s fleur-de-lys, it was also a canny reference to King Childeric as a unifying power and a revered leader in French history.

An interesting side note to this tale is that Napoleon’s homeland of Corsica was required by the Romans to pay an annual tax of £200,000 in beeswax. Whether Napoleon knew it or not, bees appear to have been his destiny.

WHAT IS YOUR SPIRIT ANIMAL?

Below is a quick guide to some of the most popular animals in jewellery and what qualities they each represent. Please note that different cultures around the world may impart different meanings to those listed below – this is simply a starting guide to the most common interpretations!

♦ BAT – Bats signify change and transition, as well communication and nurture. They are often used as symbols for transformation, camouflage and superstition.

Shop our bat jewellery HERE.

♦ BEAR – The bear is emblematic of grounding forces and strength, worshipped throughout time as a powerful totem representing courage, adversity and leadership.

Shop our bear jewellery HERE.

♦ BUTTERFLY – Like bats, butterflies signify personal transformation, as well as renewal, playfulness, the soul and matters of the heart.

♦ CAT – Cats symbolise the exploration of the unknown, balance, adventure, curiosity and that which is hidden in the darkness.

♦ COUGAR – Cougars generally symbolise leadership, responsibility, decisiveness, primal power, feminine strength and patience.

♦ COYOTE – These native American mammals are seen as both a teacher of hidden wisdom as well as an animal with humour. They are therefore often associated with trickery or mischief.

♦ CROW – The crow is linked to mystery and magic. Like the coyote, it is also a symbol of trickery, as well as luck, and is often associated with intelligence, higher seeing, mischief and destiny.

♦ DEER – The deer represents the sensitive and those with strong intuition. It has symbolically been used in art and jewellery to represent gentleness, innocence, vigilance and regeneration.

Shop our stag jewellery and deer jewellery HERE.

♦ DOG – Domesticated descendants of wolves, dogs are symbolic of loyalty, faithfulness, protection and playfulness.

♦ DOLPHIN – The dolphin represents harmony and balance, inner strength and playfulness.

♦ DRAGON – In Chinese culture, the dragon symbolises power, honour, luck and success. It is a supernatural being with no parallel for talent and excellence. Ancient tradition associates dragons with leaders of the world, due to their dominant and ambitious character traits.

♦ EAGLE – The eagle is most frequently associated with intuition, creativity, vision and healing.

♦ FROG – The frog is symbolic of transience and strongly associated with all water symbols. It is also linked to cleansing, rebirth, fertility and transformation.

♦ GOAT – Goats are believed to be gentle, mild-mannered, stable, amicable and have a strong sense of kind-heartedness and justice. They are associated with strong creativity, perseverance but head strong.

♦ HORSE – The horse represents personal drive, passion and appetite for freedom.

♦ JAGUAR – The jaguar is believed to be the gatekeeper to all unknown. It is associated with mystery, confidence, passion, change, dignity and widening perspectives.

♦ LION – The lion is the king when it comes to relentless fighters, representing courage, strength and challenge. He also symbolizes the wild and unharnessed power, as well as assertiveness and predatory feelings.

♦ MONKEY – Known for its wit and intelligence, the monkey is mischievous, curious and clever. The monkey is a sign of creativity, ingenuity and resourcefulness.

♦ OWL – The owl is emblematic of wisdom and knowledge, reality and deceit.

♦ OX – Symbol of diligence, strength, dependability and determination. Known for their honest nature, patience and persistence for progress. Female oxes traditionally represented faithful wives.

♦ PEACOCK – The peacock has always epitomised beauty and grace, as well as spirituality and self-awareness.

♦ PIG – Diligence, compassion and generosity are traits attributed to the pig. Concentration, independence and a sense of calm are also symbolic of the pig. Pigs are often seen as a symbol of good luck.

Shop our pig jewellery HERE.

♦ RABBBIT – The rabbit is considered to be quiet, gentle, skilful, responsible and kind.

♦ RAT – Quick-witted, resourceful and smart. The rat represents hard work, thriftiness as well as wealth and prosperity, particularly in business. With large litters, the rat also symbolises abundance, fertility, kindness, and expanse.

♦ ROOSTER – The rooster is associated with traits such as hardworking, resourceful, courageous and talent, whilst possessing a strong self-confidence.

♦ SHEEP – The sheep is said to symbolise innocence, vulnerability, self-acceptance and a respect of limits.

♦ SNAKE – The snake symbolises fidelity, an intuitive nature, rebirth and longevity. Moving on its belly, the snake is often associated with being grounded and patient. Historically, it has been used to represent eternal love and was a common subject for rings.

♦ SPIDER – The spider is a strong representative of feminine power and creative energy, characterised by their skilled weaving of webs and patience awaiting prey.

♦ TIGER – The primary meaning of a tiger is willpower, strength and courage. They are also associated with aggression, anger and unpredictability.

♦ WHALE – The whale is believed to be earth’s record keeper of time, symbolising wisdom, emotional healing and peace.

COMMISSIONING BESPOKE ANIMAL JEWELLERY

Now that you have a better idea of what spirit animal you might be, why not commission your own piece of animal jewellery to protect and watch over you?

We regularly created animal jewellery for many of our bespoke clients, who like us share a passion for the natural world. To date, we have worked on commissions to make lion-head earrings, a frog necklace, lobster cufflinks, an enamel butterfly necklace, alpaca earrings, kangaroo cufflinks, horse stick pins, bear cufflinks, a bee necklace, Pegasus earrings, butterfly earrings, elephant cufflinks, a kangaroo necklace and frog and scorpion cufflinks (amongst others).

If you are interested in commissioning a unique piece of bespoke animal jewellery please contact us at [email protected] to discuss your ideas and requirements. We are happy to provide you with a complimentary quote for your concept with no obligation to proceed.